It’s almost a cliché among metalheads to snicker at Metallica’s St. Anger. From the infamous “trash can” snare drum clang to the absence of guitar solos, this 2003 album has long been battered by both critics and fans like… well, Lars‘ trash can snare.

Detractors often dismiss St. Anger as an unpolished mess – a deeply flawed album from a deeply flawed group of individuals.

Yet, beneath the abrasive surface lies a bold artistic statement.

What many hear as flaws were intentional choices, aimed at capturing raw emotion and stripping Metallica’s sound to its core. Two decades on, St. Anger deserves a fresh look not as a failure, but as a misunderstood masterpiece of honesty and experimentation.

The Sound of Honest Rage

St. Anger is defined by its raw, organic production – a stark contrast to the polished, Pro-Tools-perfect sound of many modern metal albums. Nowhere is this more evident than in Lars Ulrich’s snare drum, which rings out with an unprocessed clang that polarized listeners. Far from being a studio accident, that abrasive drum tone was a deliberate artistic choice. Producer Bob Rock recalls how Ulrich discovered the sound during rehearsals and refused to abandon it: “that was the sound… and he just would not go back”.

Rock explains that this lo-fi, unvarnished drum timbre was essentially the sound of Metallica jamming in their old clubhouse – a nod to their garage roots. “It’s basically the closest to them being in that clubhouse,” Rock says, emphasizing that capturing that unfiltered vibe “kept the band together” during turbulent times.

Speaking of turbulent times, to truly appreciate St. Anger, one must consider the historical context in which it was created. By 2003, Metallica was a band at a crossroads, coming off a decade of creative exploration, personal turmoil, and fanbase division. The mid-’90s Load/Reload era had seen Metallica adopt bluesy hard-rock influences and a new image, alienating some old-school thrash fans.

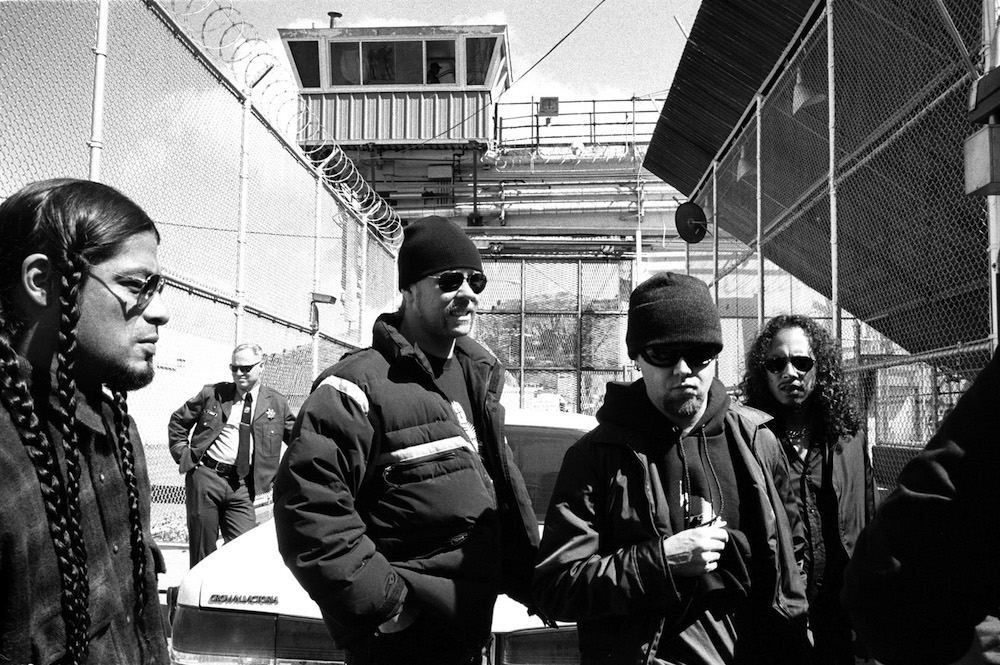

Entering the new millennium, the band faced even greater challenges. Bassist Jason Newsted had quit in 2001 amid internal strife, and frontman James Hetfield entered rehab later that year to battle alcoholism and addiction. The very future of Metallica was in question, with relationships between members strained to the breaking point. This fraught period was captured in the documentary “Some Kind of Monster“, which shows the band undergoing therapy sessions and emotional breakdowns as they attempted to write new music. Out of this chaos emerged St. Anger, essentially the soundtrack to Metallica’s near-collapse and rebirth.

Originally, St. Anger was hyped as a “return to roots” – a project that would bring Metallica back to the aggressive intensity of their ’80s thrash glory. Fans who had bristled at the band’s ’90s experiments were eager for a throwback to albums like Master of Puppets or …And Justice for All. Metallica themselves hinted in interviews that they were going “back to heavier stuff.”

However, the album that materialized in 2003 was not a simple rewind to 1986. Instead, Metallica delivered something far more unorthodox: St. Anger traded polished riffs for sludgy, downtuned guitar onslaughts; guitar solos were completely absent; song structures were long, circular, and almost hypnotically repetitive. This was Metallica reinventing itself under extreme duress, not merely imitating their younger days.

Critics of St. Anger often bemoan its “muddy” guitars and rough mix, but those too are part of the album’s ethos. Rather than layer on studio gloss, Metallica and Bob Rock stripped the production down to a visceral grind. “We wanted to do something to shake up radio and the way everything else sounds,” Rock later explained, “To me, this album sounds like four guys in a garage getting together and writing rock songs.”

What you hear are the human imperfections – the hiss of amps, fingers sliding on strings, the occasional off-kilter note. These “blemishes” give the record a live-wire authenticity. One reviewer noted that if an underground extreme metal band released an album with a similarly raw mix, the metal community would likely praise its “enduring kult-ness and lack of compromise.” In fact, “Decibel has congratulated Darkthrone for creating way shittier-sounding albums than St. Anger,” quipped columnist Kevin Stewart-Panko, pointing out the double-standard in how Metallica’s rough sound was received.

Even the much-maligned snare has its defenders on artistic grounds (this writer included). Lars Ulrich himself has stood by his choice, dismissing the backlash as “closed-minded”. He said that at that moment in time, “that was the truth” of how he felt, and he still “stands behind it 100%.” This brash “take-it-or-leave-it” attitude shines through the whole album. In an era when many metal records were starting to blend together in slick, computerized sameness, Metallica threw a wrench into the gears with St. Anger’s raw aesthetic. The result may be jarring, but it’s also refreshingly organic. It’s the sound of a legendary band bleeding in real time onto tape, with no safety net.

A Crucial Chapter in Metallica’s Evolution

Importantly, St. Anger represents Metallica exorcising their demons in real-time. The album’s creation coincided with what Lars Ulrich later described as a kind of mid-life crisis for the band. They were multi-millionaires and metal legends, but internally they were grappling with “What now? Where do we go from here?” James Hetfield was striving for sobriety and stability; Lars Ulrich was fighting to keep the band from imploding at all costs.

The result was the heaviest, most abrasive music they’d ever made – a far cry from the groovy radio rock of just a few years prior. This context explains why St. Anger sounds so visceral and unhinged. It’s the audio equivalent of group therapy: cathartic, sometimes uncomfortable, but undeniably real. The lyrics – often raw screams of frustration, confusion, and self-doubt – mirror the band’s headspace. The album cover itself, featuring a crimson fist wrapped in rope, serves as a visual metaphor for the band’s sense of being creatively confined and emotionally blocked.

When comparing St. Anger to Metallica’s earlier and later works, its unique place in their discography becomes clearer. The band’s first four albums in the ’80s were tight, thrash-metal classics – disciplined in composition despite their aggression. The self-titled 1991 “Black Album” brought a polished, anthemic sound that conquered the mainstream. By contrast, St. Anger is deliberately anti-mainstream.

In stripping away these commercial elements, Metallica made a record that is closer in spirit to garage punk or sludge metal than to the slick heavy metal of the early 2000s. It was a risky move – and indeed many fans and critics initially recoiled – but it was a necessary cleanse. After St. Anger, Metallica would regroup (with new bassist Robert Trujillo) and eventually return to a more familiar thrash-metal style on 2008’s “Death Magnetic” and beyond. In that sense, St. Anger stands as a transitional chapter: the extreme purge of emotion and noise that allowed Metallica to move forward.

In Defense of The Unforgiven Album

While St. Anger confused or even angered many listeners upon release, several critics and experts recognized the album’s bold artistic intent from the start. In fact, St. Anger initially garnered some positive reviews amid the controversy. AllMusic’s Johnny Loftus praised it as a “punishing, unflinching document of internal struggle” that “takes listeners inside the bruised yet vital body of Metallica.”

Rolling Stone’s critic likewise applauded the raw fury, declaring “there’s an authenticity to St. Anger’s fury that none of the band’s rap-metal followers can touch.” The same review explicitly appreciated the lack of commercial pandering on the record, the absence of radio singles or trendy concessions, as proof that Metallica was prioritizing expression over marketability.

Fellow artists and producers have also defended St. Anger’s artistic merit. Bob Rock – who, aside from producing, actually filled in on bass throughout the album’s recording – has been one of its most vocal champions. Having produced Metallica’s biggest hits in the past, Rock took a very different approach here and has no regrets. He loved that St. Anger “doesn’t sound like a traditional metal album whatsoever”, even if that angered purists. He drew inspiration from garage-rock revival bands of that era (like the White Stripes) who proved that “grungiest, dirtiest sounds” could connect with audiences. In St. Anger, Rock saw a chance to help Metallica “reinvent the genre” by rejecting metal’s unwritten rules and embracing a “savage, thrash-oriented sound” unlike anything on rock radio

The album found unexpected champions among legendary musicians as well. Producer Bob Rock revealed that both Jimmy Page and Jack White, of the aforementioned White Stripes fame, separately expressed their admiration for St. Anger in personal encounters. “Jack White came up to me from across the room and he says, ‘By the way, I love St. Anger. It’s an amazing album,'” Rock recounted, while Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page told him directly, “I loved St. Anger. It’s a great album.”

An Experimental Risk That Deserves Reappraisal

Perhaps the greatest argument in favor of St. Anger is that Metallica took a massive risk in making it. Rather than play it safe and churn out a crowd-pleasing sequel to The Black Album, they released an abrasive, challenging opus that defied every expectation of a “typical” Metallica album. This kind of experimentation is something we often praise in hindsight when artists break new ground. Yet St. Anger was largely rejected at the time for its audacity. It’s only with the passage of years that many have come to see its value. The album is now frequently cited as a classic case of a record that was “ahead of its time” or at least outside its time – a stance reinforced by how St. Anger’s reputation has slowly improved among some listeners.

In retrospect, St. Anger can be appreciated for what it dared to try. It stands virtually alone in Metallica’s catalog – the band never made another album like this, before or since. It captured a moment in time that will never be repeated, for Metallica or any other band. The fact that it remains polarizing is, in a way, a badge of honor; as the saying goes, “If no one hates it, then no one truly loves it either.” By that measure, St. Anger inspired real passion on both ends. When the dust settled, the album still earned Metallica a Grammy Award (for the ferocious title track) and debuted at #1 in numerous countries.

It wasn’t the commercial disaster some imagine – it sold millions and made an impact – but it also clearly wasn’t designed for mass appeal. Instead, Metallica used their megastar platform to unleash something primal and confrontational. In the process, they arguably paved the way (or at least offered validation) for other mainstream metal acts to experiment with less polished sounds. The album’s raw aesthetic prefigured a broader nostalgia for analog and “real” sound in heavy music that grew in the 2010s. In an age when Pro Tools perfection became the norm, St. Anger’s “garage band” vibe positive light by younger musicians craving authenticity.

Metallica’s St. Anger may forever be a polarizing album, but as we’ve explored, it is far more than a punchline about snare drums. Beneath its rough exterior lies a purposeful artistic core – an album that captured a legendary band at its most vulnerable and most daring. St. Anger’s raw production was not a flaw but a statement, a rebellion against the slickness of modern metal in favor of something visceral and real.

It’s easy to dismiss St. Anger for what it is not – tuneful, pleasant, polished, or traditionally “Metallica.” But it’s far more rewarding to appreciate it for what it is: St. Anger is raw catharsis on record, the sound of a band exorcising pain and finding its way back to life. In an age where so much music (even in metal) is airbrushed and risk-averse, St. Anger stands as a reminder that great art sometimes comes from stepping outside the comfort zone. Metallica stepped so far out of theirs that they alienated much of their audience – yet they also produced an album that truly has no equal in their catalog.

So the next time someone jokes about that “terrible” snare or chaotic riff salad, feel free to crank up St. Anger and hear it with fresh ears. You just might find that this misunderstood beast of an album was a masterpiece of raw emotion hiding in plain sight, waiting for listeners to finally embrace its fury for what it was meant to be

Sources:

- Tone-Talk. Bob Rock! Legendary Music Engineer/Producer with Pete Thorn as Guest-Co-Host

- Fandom. St. Anger

- Decibel. Justify Your Shitty Taste: Metallica’s “St. Anger”

- AllMusic. Metallica – St. Anger

- Talk is Jericho. Bob Rock – Why Jimmy Page Loves St. Anger