Veteran metal icons Iron Maiden swap their legendary onstage theatrics for high-end screens and CGI on their 50th anniversary tour – a bold shift that sheds light on touring costs, tech trends, and the future of live metal shows.

Iron Maiden built its reputation not just on music but on spectacle. For decades, a typical Maiden show meant elaborate sets and props: towering backdrops, stage-filling animatronics of their mascot “Eddie”, intricate set pieces, and plenty of pyro.

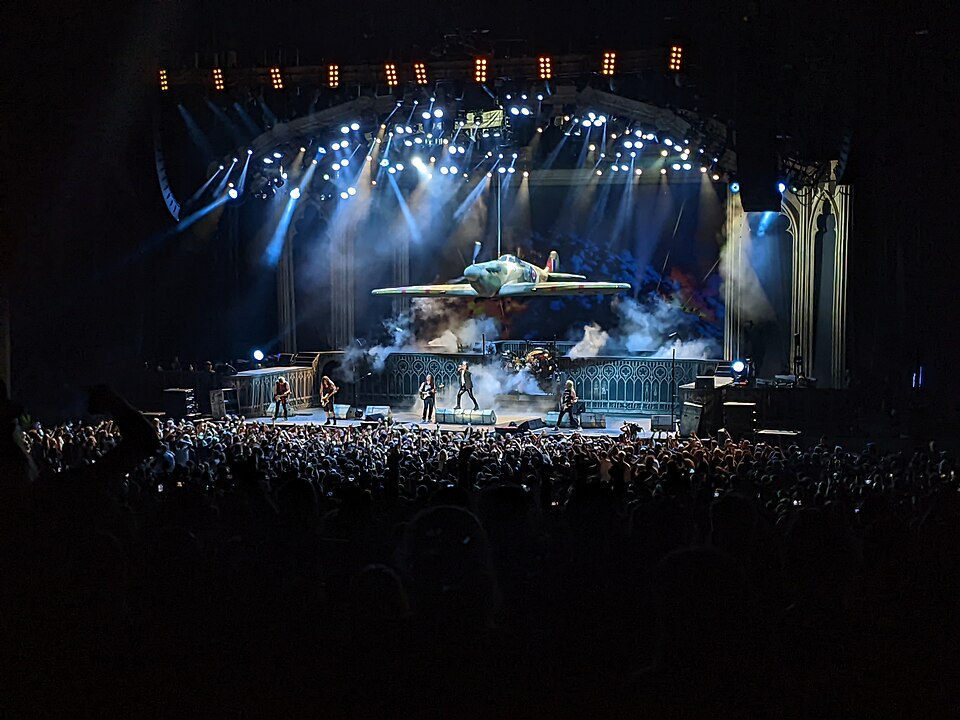

On the 2018-2019 “Legacy of the Beast” tour, for example, the band hauled a menagerie of theatrical elements: 10 different painted backdrops, a replica WWII Spitfire plane, a giant demon, an Icarus figure, a walking Eddie mascot, gothic stained-glass cathedral windows, prison bars, and more.

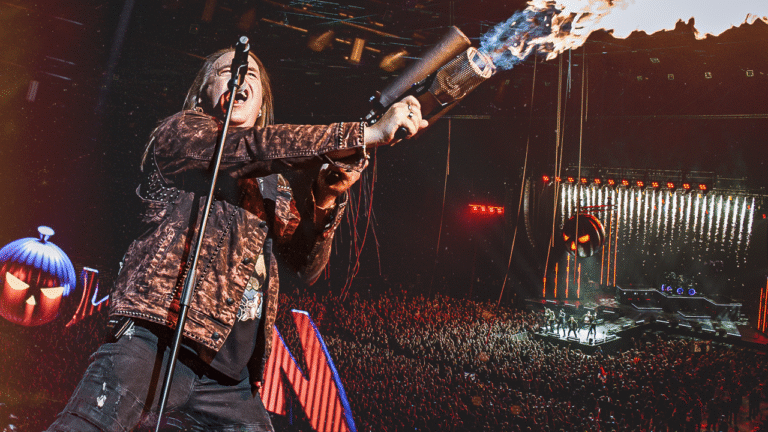

All this gave Bruce Dickinson and crew a physical playground on stage. Night after night, Bruce dueled an armored Eddie with a sword or wielded a flamethrower amid exploding powder kegs and fire pots. In Iron Maiden’s prime, real smoke and fire, tangible sets, and onstage actors in creature costumes were the norm, a heavy metal theater production as much as a concert.

That artistic nuance still carries a price: special-effects vendors, flame units, and one-of-a-kind build costs add up. In short, the old-school Maiden spectacle demanded a sizable budget for materials, manpower, transportation, and fuel. It was a price they paid to bring fans an unforgettable visual experience, but it’s easy to see how the bigger-is-better philosophy could hit a financial ceiling, especially as fuel prices, freight rates, and crew wages have only climbed since the pandemic.

The Screens Took the Stage

Fast forward to 2025, Iron Maiden’s 50th anniversary “Run For Your Lives” world tour, and the stage picture looks strikingly different. Touted as the band’s most ambitious production yet, it turned out to be a very different kind of spectacle than fans had in mind. The band has dramatically digitized its stage design, shifting away from bulky physical props toward a sleeker, high-tech setup dominated by a gigantic LED video wall and pre-rendered animation.

This enormous screen spans the back of the stage, bathing the arena in vivid imagery that changes to match each classic track. Fan-shot footage from opening night in Budapest showed the screen cycling through different incarnations of Eddie, the band’s infamous zombie-like mascot, in elaborately animated form. The entire stage is effectively an LED canvas now, providing dynamic backdrops that move with the music and story.

Crucially, this digital pivot also meant saying goodbye (at least partially) to one of Maiden’s most beloved stage traditions: the giant Eddie. In past tours, a huge Eddie creature would often emerge during the finale (often the song “Iron Maiden” itself), either as a towering inflatable or animatronic figure looming over Nicko McBrain’s drum riser. Fans lived for that moment – the literal embodiment of Maiden’s mascot joining the party. But on this tour, Eddie’s big physical final-boss iteration is largely absent, replaced by a gigantic digital avatar on the band’s eponymous song.

The Price of a Spectacle

What prompted this shift to a leaner, screen-centric production? One likely factor is cost and logistics. Touring economics in 2025 are challenging even for mega-acts. Bruce Dickinson himself recently bemoaned how concert expenses drive ticket prices “through the roof”, citing U2’s high-tech Las Vegas residency (with its 360° LED sphere venue) as an example – “it was 1,200 dollars per seat in the Sphere… I’ve got no interest in paying $1,200 to see U2.”1

While Maiden aren’t charging four figures, they are certainly mindful of getting hefty bang for their buck on tour. Replacing physical sets with digital visuals can offer efficiency gains. Imagine the difference on the road: hauling ten large backdrops, multiple statues, pyro rigs, and assorted set dressings requires extra trucks, specialized handlers, and setup/teardown time. By contrast, an LED video wall (even a massive one) packs down into road cases and travels comparatively compactly.

One can only assume that on this tour, Maiden may be running a slightly smaller convoy of trucks than before, perhaps shaving off one or two semis’ worth of physical cargo thanks to the video screen taking over duties once handled by heavy props. Cutting even a single 18-wheeler from a European tour leg translates to notable savings in fuel, driver fees, ferry or tunnel costs, and so on.

Fewer bulky props also streamlines the load-in and load-out at each venue, potentially reducing overtime hours for local stagehands and lowering the risk of freight delays (or Spitfire malfunctions!). In terms of sheer transport and labor, a screen-based show is a leaner machine.

That said, high-tech touring isn’t about to be cheap. The expense is simply allocated differently. LED screens and the media servers to run them are expensive pieces of kit. If a band doesn’t already own them, they must be rented from production vendors. Depending on size and resolution, renting a large modular LED wall can cost on the order of $1,000 to $5,000 per day2, and Maiden’s setup is likely on the higher end given its scale and quality.

There’s also the price of content creation: Iron Maiden had to invest in producing all those bespoke animations and graphics that play during the show. This likely meant hiring digital artists or studios to create 3D Eddie models, motion graphics, album art montages, and so on for dozens of songs, a substantial upfront cost that doesn’t apply when you simply paint backdrops or reuse an old Eddie costume.

In rough estimates, according to 2024 data3, high-quality 3D animation typically costs between $10,000 and $30,000 per minute, depending on complexity and style. For a band like Iron Maiden, whose average set runs about 15 songs with each lasting approximately four minutes, this could mean an investment ranging from $600,000 to $1.8 million just for the animated visuals alone.

To put this into perspective, on their last tour, “The Future Past,” the band grossed approximately $40.4 million from 432,725 tickets sold across 30 shows, averaging about $1.35 million per show4. In 2022, they ranked 26th on Billboard’s Top Tours list, grossing $76.1 million from 47 performances5. Earlier, their “Book of Souls World Tour” in 2016-2017 grossed $106 million from 104 shows6. These figures represent gross ticket sales and do not account for expenses like production, travel, and crew salaries.

There’s also a sustainability angle to consider. Many artists today are conscious of the carbon footprint of touring. Eliminating a few truckloads of gear and reducing freight weight can shrink emissions. Bruce Dickinson, an airline pilot as well as singer, knows the fuel burn of flying a Boeing 747 full of stage equipment (as Iron Maiden did on some past tours with their “Ed Force One” plane). A lighter tour isn’t only about money; it aligns with pressures to make live music more environmentally and logistically sustainable.

It’s an efficiency that some in the industry see as the future: why cart an eight-foot-tall fiberglass demon around the world, when you can project an even larger, animated demon in HD at a fraction of the transport cost?

The 2025 Maiden tour seems to pose that very question.

The New Normal?

Iron Maiden’s embrace of digital stagecraft reflects a broader trend in live music, one that could profoundly affect artists at every level. In an era when revenue from album sales has plummeted and touring is the main lifeline, efficiency and impact are king. Big legacy acts like Maiden have the budget to completely revamp their production style and invest in cutting-edge visuals. But what does this mean for the up-and-coming metal band in the clubs, or the mid-tier rock act trying to level up their live show?

On one hand, the trickle-down of technology can be empowering. Rental costs for basic LED screens have slowly become more accessible – a small venue or festival might already have video panels or projection in-house that younger bands can utilize without buying their giant video wall. In contrast to commissioning elaborate props or carrying large set pieces (which is wildly impractical on a tight van tour budget), bringing along a hard drive of cool graphics or hiring a freelance animator to make some background visuals could be a relatively affordable way for a smaller act to add theatrical flair to their gigs.

In that sense, Iron Maiden’s pivot could be seen as the democratization of spectacle: digital visuals are scalable. A club band might not afford a Spitfire replica hanging from the rafters, but they could certainly play a custom WW2 dogfight video on a screen during their equivalent of “Aces High.” Maiden’s influence might spur others to get creative, just like they did when they set the standard for what a heavy metal spectacle should look like in the 80s.

On previous tours, Iron Maiden would fly a replica WWII Spitfire above the stage during “Aces High.” In 2025, the physical plane is gone, replaced by digital dogfights on a massive LED backdrop. Such virtual effects are visually impressive while saving the band transport and setup of large props.

Some fans, however, lament the loss of tangible stage props. There’s a nostalgic charm in seeing an actual 10-foot Eddie lurch on stage, knowing a crew of humans built and operated it. Going digital can never fully replace the visceral thrill of those practical effects for some people.

We can probably expect a mix of approaches in the future: many bands will augment their shows with more video and LED elements (because the technology is there and increasingly cost-effective), while others may double down on real props as a statement of classic showmanship, or limit screen use to avoid overshadowing the performers.

In the end, Iron Maiden’s 2025 stage revolution isn’t about saying one approach is better than the other. It’s an adaptation – a response to the realities of 2025 and the tools available. It shows that even the most traditional heavy metal titans aren’t immune to change. After 50 years, Maiden is still experimenting, still taking risks on behalf of their fans’ experience. They’ve proven masters of the extravagant live show in the past, and now they’re mastering a new medium.

Whether you prefer the old-school Eddie popping out in the flesh or you’re blown away by the new-school digital firepower, one thing is undeniable: Iron Maiden remains, in spirit, as theatrical and grand as ever.

Sources:

- Blabbermouth. BRUCE DICKINSON Says Concert ‘Ticket Prices Have Gone Through The Roof’: ‘I’ve Got No Interest In Paying $1,200 To See U2’

- Hartford Rents. Complete Guide to LED Video Walls: Costs, Benefits, and Rentals

- Pixune. How Much Does a 3D Animation Cost?

- Touring Data. The Future Past Tour (2023)

- Blabbermouth. Def Leppard + Mötley Crüe, Guns N’ Roses, Iron Maiden Among Billboard’s Top-Grossing Tours Of The Year

- Wikipedia. The Book of Souls World Tour